Lluís Bertolin

Birmingham Socialist Students

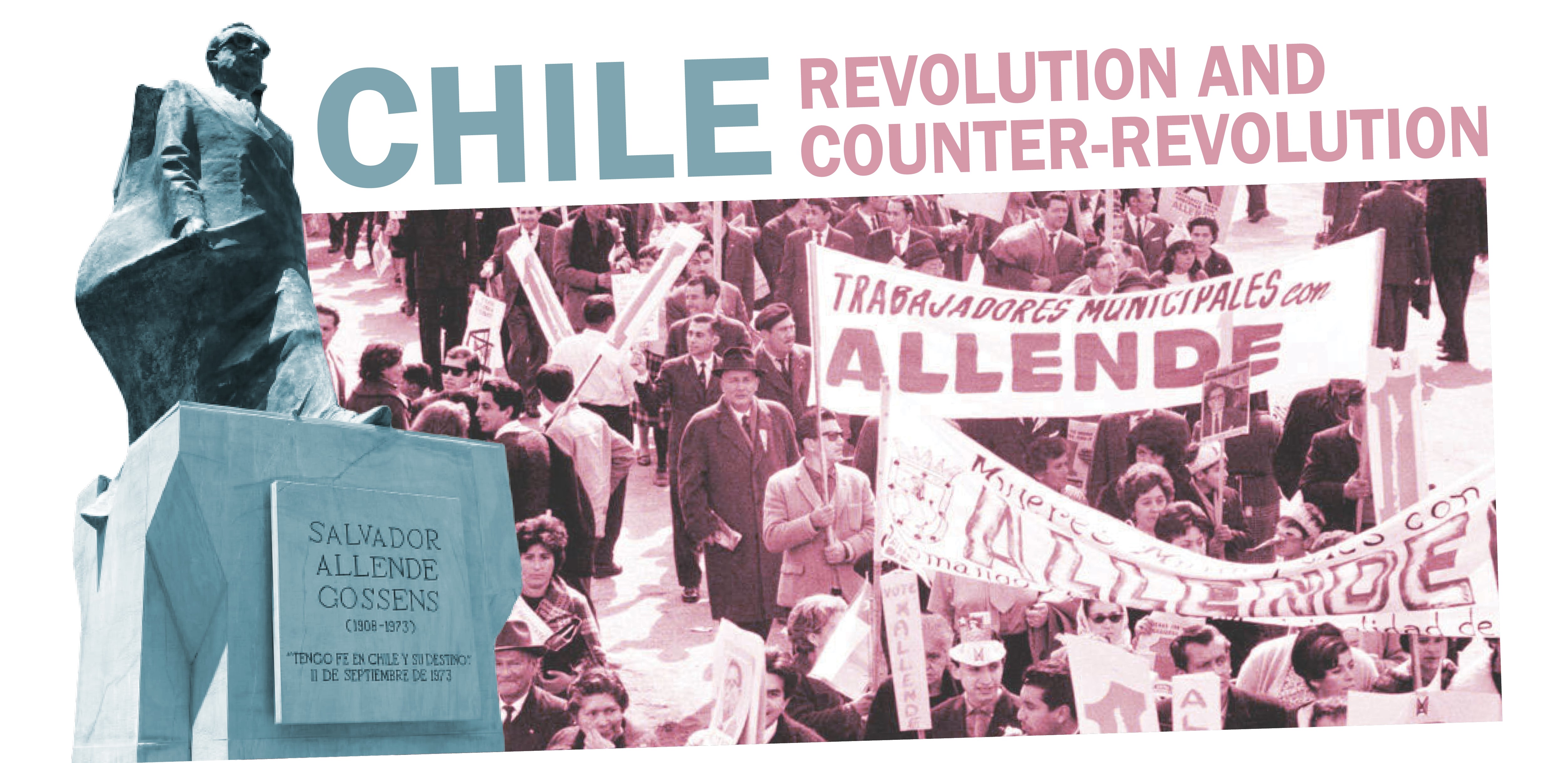

The events of Chile 1970-73 are the memory of a faded hope, a what-could-have-been, a series of events littered with lessons and inspiration. The tale of Salvador Allende´s presidency is a cautionary one; it reminds us that one cannot pluck the nails from the tiger of capitalism one at a time, and that the capitalists will take every concession and opportunity to defeat any alternative to the regimes they back. Allende´s Chile shows how much can be accomplished through struggle, workers’ self-consciousness and coordination, and how much can be lost by wavering leaderships, stageist approaches, and an unwillingness to stand your ground and fight back without accommodations to the bourgeoisie. As I heard a Chilean once say: “September is always Allende´s month”, the month of his election and the month of his downfall.

Chile and the world in the 1960s

Internationally the 1960s were a period of upheaval among the working class and youth globally, including the civil rights movement in America and the events of France in 1968, but also the 1968 movement in Pakistan against the dictatorship.

In Chile this mood for revolt found fertile soil. Since the 1920s workers’ parties had sprung up in Chile, and the country had a long tradition of workers’ organisations. Two of them were the very Stalinised Communist Party (which at that time advocated for the need for capitalist development before a socialist one was possible) and the Socialist Party (which had a programme for workers’ revolution). By 1958 already a coalition which included these left-wing parties and which would eventually become Unidad Popular (Popular Unity, UP), led by Salvador Allende, almost won the presidential elections, much to the horror of the capitalists.

By 1969 the conjunction of an economic crisis, the failed attempts of the Christian Democracy government to enact land reforms, and episodes of harsh police repression, such as the massacre of Puerto Montt, galvanised the masses and threw all parties, left and right, into a crisis. It got to the point where a section of Christian Democracy split to join Allende´s coalition! But UP was also in turmoil. The Socialist Party underwent its own split, with its left-wing leaving. A symptom of this turmoil between moderates and proper revolutionaries can be seen in the committee meeting that appointed Allende (a part of the more moderate faction and a compromise candidate): there were 12 votes in favour and 13 abstentions.

Allende’s victory in the presidential election of September of 1970 came as a shock to everyone. The moment of truth had arrived. Would Allende be able to empower the working class and lead a truly unprecedented road to socialism in Latin America? Or would he fail and be swept away amongst broken promises and dashed hopes? Reality can be a complex thing sometimes, and it was the case in Allende´s Chile that both scenarios became true simultaneously.

The reforms of Popular Unity

We cannot underestimate the impact and importance of the reforms that Allende and the UP implemented: free milk in schools, pensions increased, price controls; a sweeping programme of nationalisation in which the government took control of private industries; ironworks, the textile industry, telecommunications, banking, and the very important copper-mining industry, all nationalised. If the US companies that had owned and monopolised these industries were scared before, now they were in full-on panic mode.

Around the world, many had their eyes on Chile. The working class saw Chile as a beacon of hope, and a glimpse of what could be won in their own countries. American corporations that had seen their investments suffer after the reforms of UP also watched. And these eyes were attached to hands that would not stay idle. Already in 1970 the CIA had unsuccessfully attempted to stop Allende assuming the presidency. Now it was just a matter, they reasoned, of turning the dial up.

US intervention to oust Allende and reassert itself on the Chilean working class and economy began subtly, before acquiring a more overt and threatening nature. Chilean students were invited to study in Chicago under free-market guru Milton Freedman in order to create an ‘economic vanguard’ inside the country. Then they tried to use the Chilean parliament to block reforms. When that did not work, they tried unsuccessfully to impeach Allende.

US President Richard Nixon’s next step was clear; it was time to get violent and “make the economy scream.” An embargo was declared and US funding was poured into destabilising the Chilean economy. Not content with that, in June 1973 the US helped organise a coup against Allende, the ‘Tancazo’, which failed.

But in front of all these attacks, the working class didn’t stay passive. Not only did support for Allende rise during his tenure, but workers realised they needed to do everything possible to defend their gains from the Chilean right-wing and US imperialism, including truly revolutionary measures.

Workers began organising into the Cordones Industriales (industrial belts), meetings of elected delegates from the factories, set up from below and linked to one another. The activity of the Cordones was truly revolutionary: they took control of factories and workplaces, organised food distribution to prevent speculation, and led defence squads against the fascist paramilitary of Patria y Libertad.

Soon the Cordones developed their own political programme independent of the parties: they supported Allende conditionally, insofar as he carried out the will of the mobilised masses, and called for the expropriation of all monopolies, the introduction of workers’ control to the whole of the economy, wage increases, land expropriation, and a popular assembly to replace the Chilean parliament. The political independence of the Cordones and their autonomy worried the parties constituting the UP.

Wavering leadership

Despite being the architects of these massive reforms, the constituent parties of UP made very serious mistakes that would prove fatal. The leaders of the UP feared the politically conscious and independent Cordones, and moved to suppress them, despite their being the main strength defending the government and reforms. The reason for this suppression was the policy of the UP to try to secure itself by reaching deals and agreements with the bourgeoisie, erroneously believing there to be a ‘left-wing’ current amongst the ruling class that could be appealed to.

But the more left-wing elements of UP also made very serious strategical mistakes. They failed to reach out and appeal to rank-and-file soldiers. There were bases of support already there, and many more could have been won over to the revolutionary movement, with the potential to act as a firewall against the events that actually came to pass.

The coup and its aftermath

Allende unwittingly signed his own execution very early on into his tenure, promising not to touch the top army officials, nor to move against the armed forces. This promise, loyally fulfilled, would allow this same army to move against Allende and the working class.

The build-up to the coup was anything but secretive. Everybody knew another coup, again with US support, was coming. Just a week before the coup there were huge demonstrations of workers demanding that Allende arm the working class to defend against a potential coup. But despite this, there was a complete lack of preparations on the part of the government and the UP parties to defend themselves from the coup.

Quite the contrary, Allende tried to appease the potential plotters, unwittingly making them more influential and powerful. The coup had to deal with a part of the army, which was in favour of Allende and tried to blow the whistle on the coup. Allende abandoned them to appease the top brass. These whistleblowers were court-martialled and executed. When the coup happened its leader, Augusto Pinochet, was a minister, appointed by Allende himself!

The 11th of September coup that brought down Allende´s government was a terrible sight to see. Pinochet applied a shock-and-awe policy in militarily seizing a country that had historically been politically stable. The workers, who were left isolated, unarmed, and deprived of leadership, were not able to stop the coup.

The repression of the Pinochet regime was clinical and targeted, and included tortures, mass imprisonments and summary executions. The beacon of light of Chile turned into a well of darkness, with a brutal application of neoliberal policies throughout the 1970s and 80s, including removal of price controls, privatisation, and spending cuts.

Lessons for the future

The experience of Chile under Allende is forever etched into the collective memory of the Chilean working class and socialists around the world. The question is what lessons to draw from it.

It should be clear that UP, notwithstanding their important reforms, failed in walking the walk after talking the talk. No matter how revolutionary your pamphlets are, in certain historical moments what is needed are deeds and decisive action. When the Cordones provided such action and such deeds, they were opposed. Socialist parties must act as conduits for the aspirations and interests of the working class, and when the working class is self-conscious enough to launch itself into revolutionary struggle, it is a fatal mistake to try to contain them.

Another lesson is that one cannot wrestle control from the ruling class one measure at a time. The ruling class had to have all their power and control removed for the reforms of the UP to be defended and expanded.

Allende learned all too late that in the fight to transform society, compromise with the ruling class is impossible, and when conditions favour them, they will attack and in one fell swoop demolish all the work that has been done.

The ruthlesness of the ruling class in defending their rule and system has been demonstrated time and time again throughout history. Even the recent driving out of Jeremy Corbyn from the Labour Party in Britain is an example.

If we do not learn from the lessons of the past, we shall always be at the mercy of those who do. 50 years on, the events of Chile ought to be in the heads of anyone wishing to get rid of capitalism and move on into a socialist world. However, Chile also showed the enormous power and determination of the working class to change society once it moves into action, and the opportunities which will open up to fight for socialist change in the 21st century.

It doesn’t have to be like this – we need a socialist world!

Get the latest issue of Socialist Student, the magazine of Socialist Students, to read this article and more. Written and edited by members of Socialist Students.

Available from our resources page, or to purchase from your local Socialist Students group