Mila Hughes

Coventry Socialist Students

As the capitalist system continues to lumber from crisis to crisis, with many countries plagued by inflation, poverty, and war, there has been a renewed interest in the two most significant events from human history that saw the complete overthrow of capitalism and landlordism by huge mass movements – the Russian and Chinese Revolutions of 1917 and 1949. From studying the huge achievements of these two revolutions – and the reasons for the bureaucratic dictatorships that ultimately arose from them – we can draw many lessons which are vital to guiding today’s movements for socialist change.

Russia 1905-1917: A workers’ uprising

The seeds of the 1917 revolution started in the revolutionary events of 1905. After Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-05, mass political unrest and a strike wave led by the working class spread across the Russian Empire. This was against the Tsar and the ruling class which maintained an oppressive feudal regime with no room for workers’ or peasants’ representation.

During the course of the revolution, workers in struggle created ‘soviets’ – democratic councils of workers and soldiers – to democratically discuss the key issues and tactics of the struggle. Although the 1905 revolution failed to overthrow Tsarism, the experiences of the 1905 revolution were important in demonstrating the power and centrality of the working class in the fight against capitalism. Lenin and Trotsky would later refer to 1905 as the ‘dress rehearsal’ for the 1917 revolution.

12 years later in February 1917, women workers walked out of their factories on International Women’s Day protesting against Russia’s involvement in the slaughter of the First World War and against food shortages. They were soon joined by thousands of other workers, who extended their appeals to soldiers and sailors to join them.

The February revolution forced the Tsar to abdicate. A Provisional Government was established which governed Russia in the interests of the small capitalist class, promising full elections at a later date. Unlike the soviets which had reemerged over the course of the February revolution, the Provisional Government was unelected and quickly shown to be unable to solve the basic questions facing the Russian working class and masses.

The capitalist class in Russia delivered nothing for the working class, who had been the key force in achieving the February overturn. Russia’s involvement in the war dragged on. Food prices continued to increase while wages collapsed. Meanwhile, the weak and small capitalist class – in Vladimir Lenin’s words “tied to Tsarism by a thousand threads” – was unable to play a politically independent role and deliver land reform for the peasantry.

By October 1917 the soviets, democratically representing the Russian working class, were firmly won over to the Bolsheviks through the slogan of ‘bread, peace and land’, alongside the Bolsheviks’ tireless campaigning to put the working class at the head of the struggle to transform society. After leading the defence against an attempted reactionary military coup in August, the soviets, now led by the Bolshevik party, organised a mass revolutionary capture of power known as the October Revolution.

October 1917 marked the first time in human history that the working class took political power into its own hands and laid the basis of a new socialist society. The banks, monopolies, major industry and land were all taken into democratic workers’ control and management and, for the first time ever, the majority democratically planned society’s resources to meet the needs of all.

October 1917 marked the first time in human history that the working class took political power into its own hands and laid the basis of a new socialist society.

Under the new workers’ government all decision-making was done through democratically elected regional and national soviets (councils of workers, peasants and soldiers). Representatives were paid an average worker’s wage and subject to instant recall at any time by those who elected them.

Russia was quickly taken out of the First World War to the jubilation of millions. The example of the revolution was internationally contagious. London dock workers refused to load armaments meant to be deployed against Russia and revolution swept Europe.

Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky – the leaders of the October 1917 revolution – understood that the fate of the Russian revolution was inexorably tied up with the success of socialist revolutions internationally, particularly in the advanced capitalist economies of the West. That’s why, despite invasion, civil war and food and resource shortages, the Bolsheviks organised the first conference of the new Communist International to bring together the different socialist groups around the world to spread the revolution.

But Russia at this stage was still an extremely poor, undeveloped country. Economic isolation, the destruction of the First World War and the violent intervention by foreign capitalist armies to crush the Russian working class added to the bitter conditions.

The defeats of revolution in Europe, particularly in Germany, primarily because of the lack of a revolutionary party of the calibre of the Bolsheviks, added further to the economic and political isolation of the Russian Revolution. As shortages continued, and hundreds of thousands of workers and Bolshevik leaders perished as a result of the civil war, a bureaucracy developed within Russia with Stalin at its head which, although it ultimately rested on the nationalised planned economy, increasingly undermined and eventually destroyed workers’ democracy.

But none of this happened without a struggle. In 1923, Trotsky’s Left Opposition was established to fight this growing bureaucratisation and to continue the fight for international revolution and workers’ democracy.

China 1949: Tainted from the start

Stalin’s direction and policies at the time resulted in disasters for the working class internationally. This included in the revolutionary events which developed in China.

Like in Russia, the vast majority of the population in 1920s China were peasants, with huge urban and industrialised centres in the East. In 1925, revolutionary events erupted as the working class in the urban centres of Shanghai, Guangdong, and Wuhan rose up against landlordism and capitalism. Trotsky put forward that only the working class acting politically independently from the capitalists could lead the masses, including the numerically massive peasantry, in a successful socialist revolution.

Instead, under the direction of the now Stalinist-led Comintern, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), entered an alliance with the nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) party to fight against the remaining forces of the old feudal regime in China.

This mistake proved fatal for the Chinese working class. In 1926, the KMT massacred striking workers in Canton, including 30,000 CCP members, and established a military dictatorship. After this setback, the CCP made a conscious turn away from the working class and instead based itself increasingly on the peasantry. By 1930, the percentage of party membership that were workers had dropped massively.

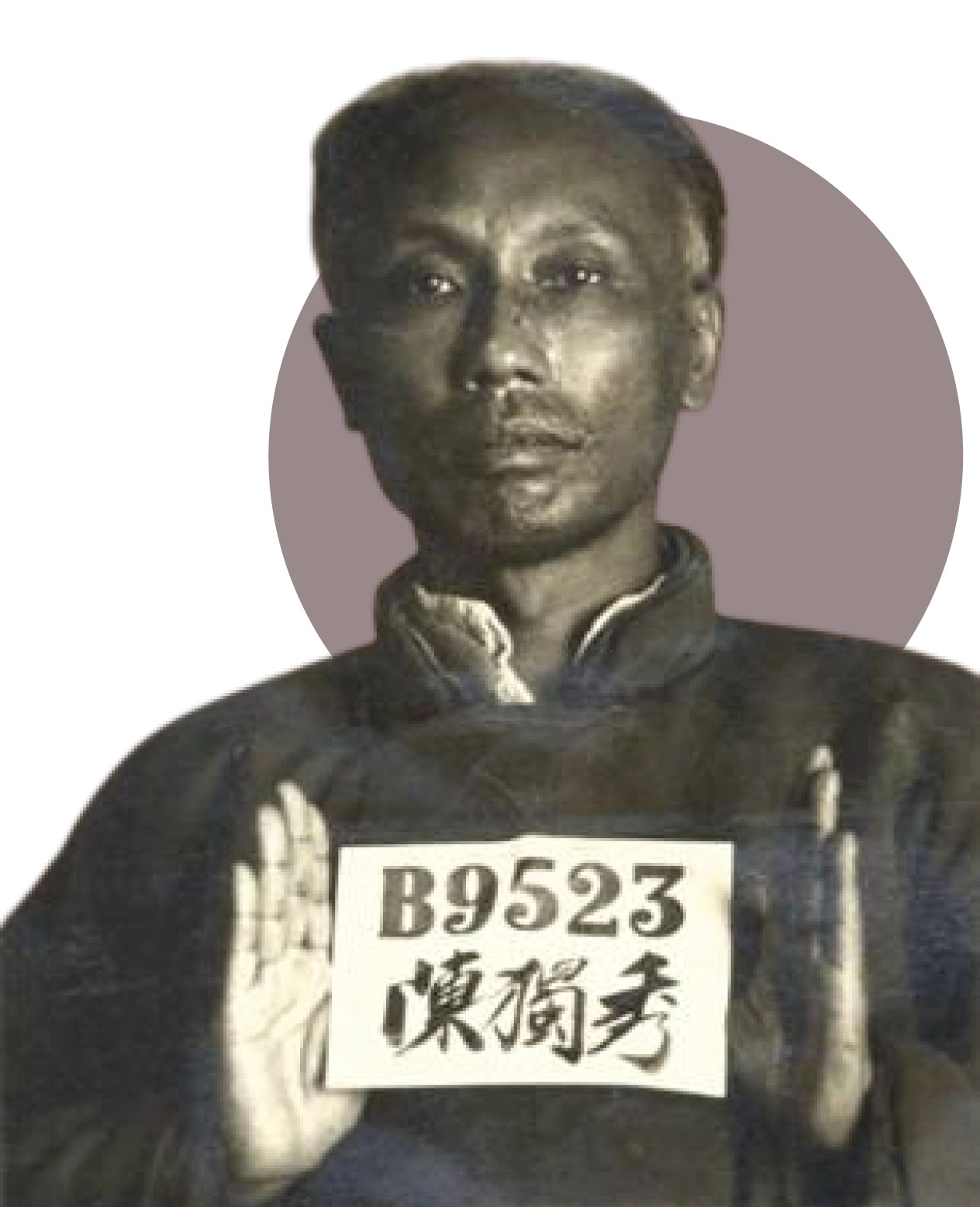

The Comintern meanwhile didn’t recognise this defeat until 1928. When it did, it pointed the finger at the CCP leaders, mainly Chen Duxiu – who had opposed the merger with the KMT and later became a co-thinker and supporter of Trotsky and the Left Opposition.

The Russian Revolution had been successful because of the existence of a revolutionary party – the Bolsheviks – with a programme and methods to fight for socialist transformation, which recognised the centrality of the working class in fighting for socialist change.

No such clear-sighted party or leadership existed in China. The leaders of the CCP politically took their line from Stalin and the bureaucracy in Russia. They were petrified of a genuine socialist regime of workers’ democracy being established on their doorstep, lest it gave confidence to the Russian working class to overthrow the bureaucracy in Russia. Stalin and his acolytes sought to use the Comintern not to spread socialist revolution internationally, as Lenin and Trotsky fought to, but to temper the revolutionary processes which were unfolding within China to protect their power and privileges at home.

In 1949 the CCP defeated the KMT in the civil war, thus marking the beginning of the overthrow of capitalism and landlordism across China. The lack of trust that the CCP leaders had in the working class and their focus on the peasantry inevitably led to the bureaucratic character of the regime produced by the revolution in China. Mao Zedong, leader of the Red Army and CCP president at the time, was a self-proclaimed ‘Stalinist’, modelling the revolution on the bureaucratic planned economies of Stalinism.

While the Russian Revolution degenerated in isolation after the failure of revolutions internationally, the Chinese revolution of 1949 was bureaucratically tainted from the start.

Despite the absence of democratic workers’ control of the economy, the new planned economy gave a small glimpse of what could have been possible under genuine democratic workers’ control. Land was redistributed to the peasants. Social security in employment and housing were introduced for Chinese workers. Arranged marriages were banned and literacy skyrocketed. Industrial production expanded at a rate greater than that of any other Asian country at the time.

Despite the absence of democratic workers’ control of the economy, the new planned economy gave a small glimpse of what could have been possible under genuine democratic workers’ control.

Socialism needs democracy like the human body needs oxygen, Trotsky once wrote. In the 70s, after Mao’s death, as the zig-zag policies of the bureaucracy continued to hamper the further development of the planned economy in China, the CCP turned increasingly towards the market to try and further stimulate the Chinese economy, and gradually reintroduced more and more elements of capitalism into society. In modern China the planned economy has for the most part been dismantled, although the authoritarian CCP still attempts to maintain a firm grip over the direction of the economy and the activity of private companies.

In Russia, following Lenin’s death in 1923, the growing bureaucracy organised around Stalin used brutal methods to maintain power, annihilating the Left Opposition and the original leaders of the October revolution, including the murder of Trotsky in Mexico in 1940. Stalin created a ‘river of blood’ between his regime and the October 1917 revolution.

Nonetheless, despite the crushing of workers’ democracy by the Stalinist counter-revolution within Russia, the fundamental gains of the October revolution – the nationalised planned economy – continued to exist, right up until Stalinism collapsed under the weight of the parasitic bureaucracy in the 1990s.

Both the Russian and the Chinese revolutions provide invaluable lessons for socialists in 2023 fighting to consign the barbarity of capitalism to history and to build genuine socialism in Britain and across the world.

It doesn’t have to be like this – we need a socialist world!

Get the latest issue of Socialist Student, the magazine of Socialist Students, to read this article and more. Written and edited by members of Socialist Students.

Available from our resources page, or to purchase from your local Socialist Students group