U’Semu Makaya

Birmingham Socialist Students

Racism in Britain today takes many forms; whether physical or verbal abuse, disparities in the workplace, discrimination in education, inequality in housing, or antagonism from all branches of the law, countless people fall victim to the plague that capitalism has enabled to fester.

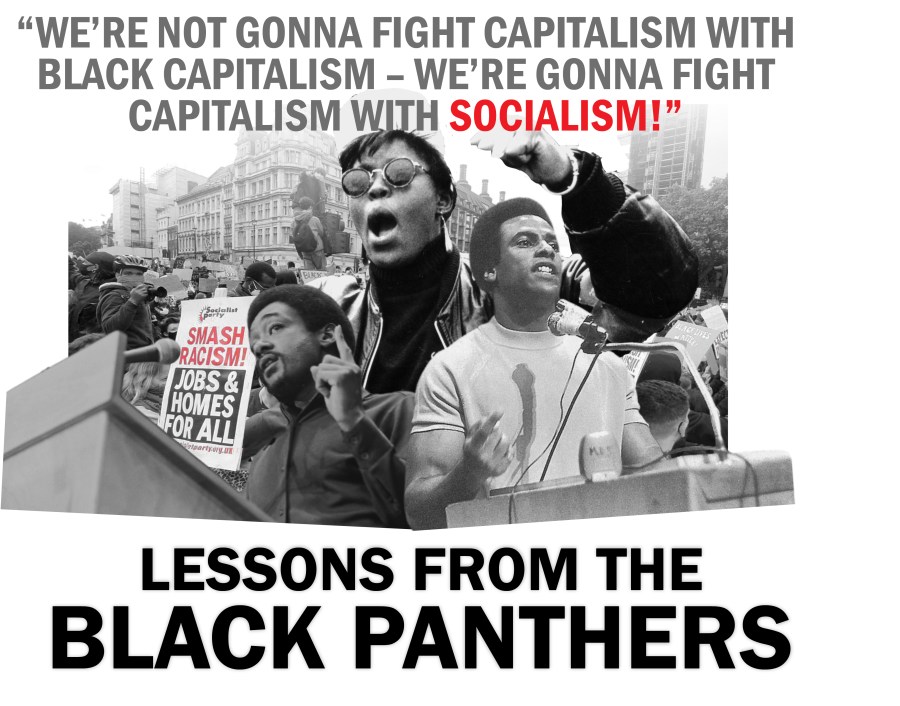

For socialists the question is how we fight to rid society of the grotesque stain of racism. We take inspiration from Black Panther leader Fred Hampton’s demand that to finally eradicate racism, poverty and inequality, socialist change is needed: “We’re going to fight racism not with racism but we’re going to fight with solidarity. We say we’re not going to fight capitalism with black capitalism but we’re going to fight it with socialism.”

Capitalism is a system based on exploitation and oppression. Racism was intrinsic to the development of British capitalism through the Atlantic slave trade. Racism and racist ideas are used to maintain capitalism today, as a means of attempting to sow division within the working class as the bosses seek to attack the wages and living conditions of workers from all different backgrounds.

For socialists, the fight against racism is bound up with the struggle to end the system of capitalism which perpetuates racist division. Socialists fight to unite workers of different backgrounds in a common struggle against big business and their system of capitalism through a socialist programme.

Studying previous movements against racism is vital and must include the work of the Black Panther Party.

The Black Panther Party, initially The Black Panther Party for Self-Defence, was founded by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton in October 1966 in Oakland, California. The party was described by the FBI’s infamous J. Edgar Hoover – witch-hunter of socialists, trade unionists, Black activists, LGBTQ+ workers (so-called enemies of the US capitalist state) – described the Panthers as “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country” in 1969.

Racism, poverty, and capitalist hypocrisy

The Black Panthers’ inception was preceded by the migration of over five million Black people from the Southern states to the Northeast, Midwest, and West during the Second World War. With this came the harsh revelation of the hypocrisy behind the US government’s war propaganda. While the American ruling class preached of a crusade against the racism of the Nazis, within the US, continued the subjection of the Black population, many of whom would have been veterans of the war themselves or families of its victims. From segregation under Jim Crow laws, to abject poverty, discrimination and bigotry of the bosses, and continued brutal violence at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan, racism remained a tool in the hands of the American ruling class.

Frustrations exploded in the 1954-68 civil rights movement. Partially inspired by liberation movements against Western imperialism worldwide, Black people across the US were roused to action against their continued disenfranchisement under US law. The efforts of this movement urged the gradual repeal of many of the laws that had previously allowed racial segregation and discrimination, culminating most prominently in the passing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which banned, on paper, discrimination on the basis of race in areas such as education, business, and housing.

Despite this victory in the legal arena, the economic realities of Black Americans’ lives saw little to no improvement in the following years. Black unemployment continued to steadily increase during the late 1950s and early 60s, 32% of Black Americans remained firmly below the poverty line, 20% had spent time in prison by 1971, and were generally victims of violence at the hands of the police and groups like the Third Ku Klux Klan.

The Black Power movement

Against this backdrop, among a new politicised generation of young Black people, the civil rights movement was succeeded by that of Black Power. Prominent activists in the late 60s and early 70s, including some heads of the civil rights movement, rejected what were perceived to be the more moderate tactics of the civil rights movement, with some even adopting socialist ideas in the recognition of capitalism’s role in the continued oppression of the Black population.

Malcolm X in particular, whose ideas are often misrepresented in official historical narratives of the civil rights movement, increasingly developed interest in socialist ideas during the later years of his life. Previously following the Black nationalist ideas of the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X became more specifically critical of capitalism. “You can’t have capitalism without racism” Malcolm X said, drawing the links between the divide and rule tactics of the capitalist system.

The wider Black Power movement had in large part adopted the ideology of Black nationalism, inspired by organisations like the Nation of Islam and Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA), the latter having seen its heyday in the late 1910s. Black nationalism argued for the organisation of Black people fighting racism, separate and in isolation from workers and young people of different backgrounds. In reality, these ideas served to potentially strengthen divisions amongst workers and cut across the building of a united working-class fightback against racism and capitalism.

The UNIA’s popularity after the mid-1920s declined as an increased tempo of class struggle, particularly in the 1960s, united workers of different backgrounds in a common struggle against the bosses and capitalism.

What made the Panthers different was its direct engagement with the material realities of working class Black Americans and through placing their grievances within the context of class struggle – Bobby Seale famously evoked strike action when discussing the necessity of a wider workers’ movement to dismantle the “boss class”, declaring that “unity is strength”, as he decried those “[obscuring] the struggle with ethnic differences [as]…aiding and maintaining the exploitation of the masses.”

These ambitions were limited to an extent by the continued exclusion of Black people from some areas of the wider labour movement, hence the Panthers’ encouragement of political organisation solely within Black communities. But their commitment to building a united movement with workers of different backgrounds was demonstrated in their collaboration with political bodies representing other ethnic groups, such as the Puerto Rican Young Lords of New York or the Southern white Young Patriots of Chicago, as well as their work with white activists during the Vietnam War.

Class demands and community defence

The Panthers’ down-to-earth commitment to issues facing working-class Black people was exemplified in their policy and action. Their ten-point programme included demands for full employment, decent housing, free healthcare, education reform, an end to all wars of aggression, prison abolition, and “an end to the robbery by the capitalists of our Black and oppressed communities.”

To those Black nationalists who refused to participate with the Panthers, and who accused them of being ‘engrossed with oppressor country radicals, or white people, or honkies’, Hampton replied with an unequivocal class response: “First of all we say primarily that the priority of this struggle is class… It was one class, the oppressed class, versus those other classes, the oppressor. And it’s a universal fact…Those who don’t admit to that are those who don’t want to get involved in a revolution, because they know as long as they’re dealing with a race thing, they’ll never be involved in a revolution”.

The party’s chief activity was the defence of Black communities against the brutality of the police – monitoring officers while armed to ensure that Black people’s civil rights were respected – but they also made major efforts towards the establishment of free food, clothing, and healthcare programmes in poor communities. The Panthers also ensured the inclusion of women in their activism and organisation.

The Panthers reached the peak of their influence in 1970, leading the US ruling class to increase its use of police repression – thirty-nine Panthers, most famously Fred Hampton and Bobby Hutton, were killed by police and many hundreds more arrested. Sabotage by the FBI’s illegal COINTELPRO projects also fomented much of the infighting that plagued the party in its later years until its dissolution in 1982.

While state repression undoubtedly played a large part in the downfall of the party, it is necessary to recognise that it had its own political and organisational shortcomings as well. Although it had considerable influence in Black communities, the party was not oriented consistently to the working class, instead mostly targeting the unemployed. This meant that, despite the party’s valuable work, it sank little roots amongst the organised working class and within the workplaces, weakening their ability to build a powerful united working class movement to really challenge American capitalism.

This was combined with a tendency to substitute mass organisation for the Black Panthers’ own activities, in particular its armed demonstrations. As Huey P. Newton later reflected, the result was a “revolutionary vanguard” with little interest in involving or encouraging the masses in its work, with the party often “operating outside the…fabric” of the communities that it occupied.

The experience of the Black Panthers provides vital lessons for those looking to build a mass movement to defeat racism and capitalism today. The explosion of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 in the US, Britain and internationally demonstrated a new generation of young people drawing the links between the racism Black and Asian people face on a daily basis and the profit-driven capitalist system.

Socialist Students stands for the building of a united and common working-class struggle against the capitalist system which has racism woven into its DNA, and the struggle for a socialist world free from all forms of racism, bigotry and division.

It doesn’t have to be like this – we need a socialist world!

Get the latest issue of Socialist Student, the magazine of Socialist Students, to read this article and more. Written and edited by members of Socialist Students.

Available from our resources page, or to purchase from your local Socialist Students group